On my reading shelf, these days is The New Yorker’s “The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs“. Featuring rich imagery, illustrations, articles, short stories and cartoons, (all canine-themed) that have been featured in the iconic pages of the legendary weekly magazine.

The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs celebrates our bond with the only animal species that have somehow believed in our egoistical notion of being a demigod.

The anthology features great writings by the likes of Malcolm Gladwell, James Thurber and Roald Dahl on dogs, there’s even a profile on Rin Tin Tin! We also get to know about the dogs labelled as bad by society, perhaps an insight into our own selves.

And in some of these writings, divided into four sections — Good Dogs, Bad Dogs, Top Dogs, and Underdogs — touching upon themes like love, family, grief, this 400-page tribute is a must-read for dog lovers!

A few words about you. You bought this book: several hundred pages on dogs. You are, in other words, as unhealthily involved in the emotional life of dogs as the rest of us. Have you wondered why you bought it? One possible answer is that you see the subject of man’s affection for dogs as a way of examining all sorts of broader issues. Is it the case of a simple thing revealing a great many complex truths?

We do a lot of this at The New Yorker. To be honest: I do a lot of this at The New Yorker — always going on and on about how A is just a metaphor for B, and blah, blah, blah. But let’s be clear. You didn’t really buy this boo because of some grand metaphor. Dogs are not about something else. Dogs are about dogs.

Malcolm Gladwell, foreword ‘The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs’

My pick of the lot was this paragraph in Dog Days, by Marjorie Garber:

Of course, the behavior of some of these animals, if it were to be faithfully followed by human beings, would strike us as distinctly odd and perhaps psychologically unsound. It’s one thing for Hachiko to meet his master’s train for nine years; it’s another for a bereaved human being to do so. Get on with your life, we say, and we mean it. But we can demand—and receive—from dogs a highly gratifying devotion that we no longer feel comfortable about demanding from one another. In addition, these icons of absolute fidelity offer us a sense of scale. The dog, by being “superhuman” in realms like constancy and loyalty, gives us permission to temporize, vacillate, and even fail.

How profound!

Whoever could have driven worldly sense into Hachiko? The dog who waited by the train station a decade and counting, patient as pregnancy, for the Professor who could never return. Move on, your master is dead. You loved him. Shibuya knows you did. Heck! Japan knows you did. But why come to the train station? Why keep waiting for someone who would never return?

Because dogs know love like we humans often don’t. They are indeed the scale.

This poem by Wislawa Szymborska, the great Polish poet also hits all the right chords.

Monologue of a Dog Ensnared in History

There are dogs and dogs. I was among the chosen.

I had good papers and wolf’s blood in my veins.

I lived upon the heights inhaling the odors of views:

meadows in sunlight, spruces after rain,

and clumps of earth beneath the snow.

I had a decent home and people on call,

I was fed, washed, groomed,

and taken for lovely strolls.

Respectfully, though, and comme il faut.

They all knew full well whose dog I was.

Any lousy mutt can have a master.

Take care, though — beware comparisons.

My master was a breed apart.

He had a splendid herd that trailed his every step

and fixed its eyes on him in fearful awe.

For me they always had smiles,

with envy poorly hidden.

Since only I had the right

to greet him with nimble leaps,

only I could say good-bye by worrying his trousers with my teeth.

Only I was permitted

to receive scratching and stroking

with my head laid in his lap.

Only I could feign sleep

while he bent over me to whisper something.

He raged at others often, loudly.

He snarled, barked,

raced from wall to wall.

I suspect he liked only me

and nobody else, ever.

I also had responsibilities: waiting, trusting.

Since he would turn up briefly, and then vanish.

What kept him down there in the lowlands, I don’t know.

I guessed, though, it must be pressing business,

at least as pressing

as my battle with the cats

and everything that moves for no good reason.

There’s fate and fate. Mine changed abruptly.

One spring came

and he wasn’t there.

All hell broke loose at home.

Suitcases, chests, trunks crammed into cars.

The wheels squealed tearing downhill

and fell silent round the bend.

On the terrace scraps and tatters flamed,

yellow shirts, armbands with black emblems

and lots and lots of battered cartons

with little banners tumbling out.

I tossed and turned in this whirlwind,

more amazed than peeved.

I felt unfriendly glances on my fur.

As if I were a dog without a master,

some pushy stray

chased downstairs with a broom.

Someone tore my silver-trimmed collar off,

someone kicked my bowl, empty for days.

Then someone else, driving away,

leaned out from the car

and shot me twice.

He couldn’t even shoot straight,

since I died for a long time, in pain,

to the buzz of impertinent flies.

I, the dog of my master.

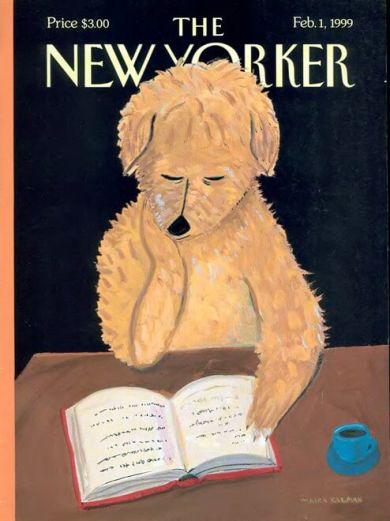

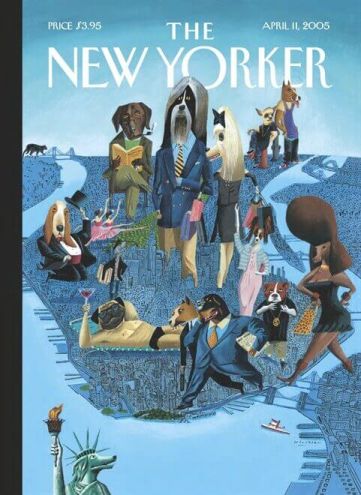

The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs covers

The copious collection also features full-blown covers of past magazine covers taking us down memory lane.

And also, the delightful dog cartoons that have earmarked The New Yorker since early days:

By the way, there’s also another collection by The New Yorker called The Big New Yorker Book of Cats. Humans, you see, aren’t as loyal as us dogs.